Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

While the COVID-19 pandemic evolved largely in the last quarter of the 2019–20 financial year, it has had a significant impact on the operations of the Family Court as recorded in this Annual Report.

There was a period of significant upheaval and adjustment at the end of March and beginning of April, during which the Court shifted to electronic hearings. The presence of COVID-19 also necessitated the postponement of the Summer Campaign, aimed at finalising long-term family law cases through a series of callovers and enhanced ADR.

The Court has used its best endeavours to continue finalising as many cases as possible, and, to the credit of judges and staff, has maintained a clearance rate of 99 per cent across all applications.

Despite this, there are certain hearings, such as trials in particularly complicated matters, that have not been able to proceed. This is due to the inherent nature of conducting proceedings electronically, including the unpredictability of the technology and internet connection of the parties and witnesses, the added difficulties for some unrepresented litigants or those parties requiring interpreters, the impact of stay at home restrictions and the additional time consumed to conduct an electronic hearing compared to a face-to-face hearing. These effects will continue to be felt into the 2020–21 financial year.

Snapshot of performance

| TIMELY COMPLETION OF CASES | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Target |

Result 2019–20 |

Target status |

|

Clearance rate of 100 per cent |

The clearance rate was 99 per cent |

Not met |

|

75 per cent of judgments to be delivered within three months |

83 per cent of judgments were delivered within three months |

Met |

|

75 per cent of cases pending conclusion to be less than 12 months old |

65 per cent of cases pending conclusion were less than 12 months old |

Not met |

In 2019–20, the Family Court achieved one target under timely completion of cases and was unable to achieve two. However it is noted that, but for the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Court is likely to have met the 100 per cent clearance rate target.

The annual performance statement for the Family Court is included as part of the Federal Court of Australia’s 2019–20 annual report.

Analysis of performance in 2019–20

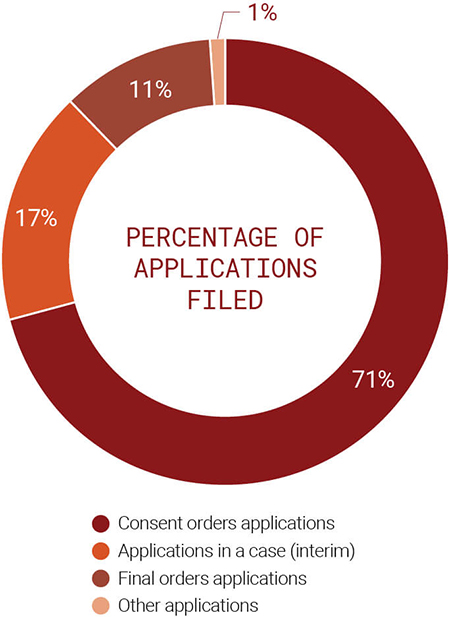

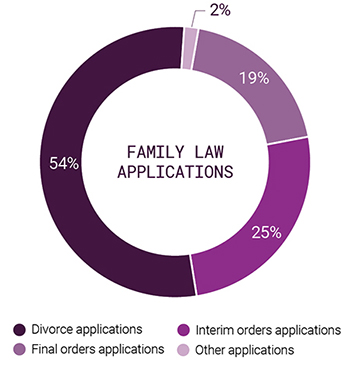

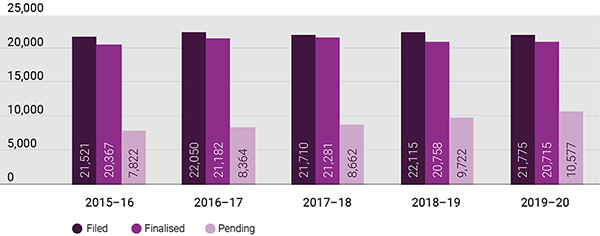

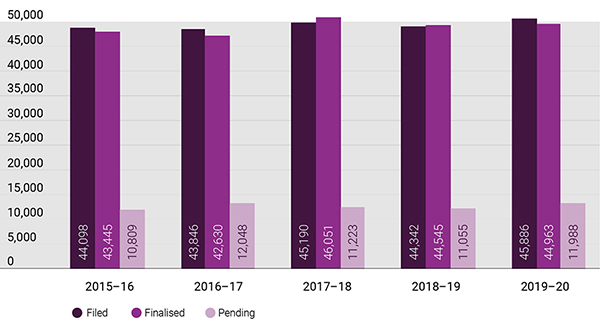

The Family Court deals with the most complex and difficult family law cases. Table 3.2 and Table 3.3, and Figure 3.1 and Figure 3.2, show a summary of the applications filed in the original jurisdiction of the Court in 2019–20.

The Court received a 7 per cent increase in the number of Final Order Applications filed, an 8.2 per cent increase in the number of Applications in a Case filed and a 7.5 per cent increase in the number of Applications for Consent Orders filed during 2019–20 compared to 2018–19.

|

Application/ case type |

Filed |

Finalised |

Pending |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Consent orders applications |

14,908 |

14,946 |

1,318 |

|

Applications in a case (interim) |

3,500 |

3,216 |

1,860 |

|

Final orders applications |

2,382 |

2,394 |

2,952 |

|

Other applications |

264 |

231 |

217 |

|

Total |

21,054 |

20,787 |

6,347 |

|

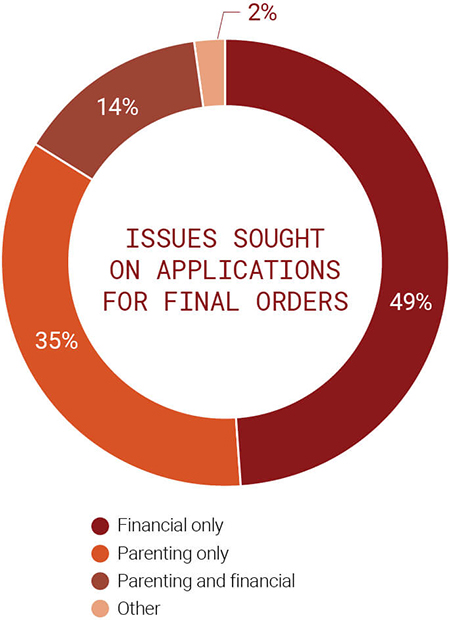

Issues sought on applications for final orders |

|

|---|---|

|

Financial only |

49% |

|

Parenting only |

35% |

|

Parenting and financial |

14% |

|

Other |

2% |

Case attrition

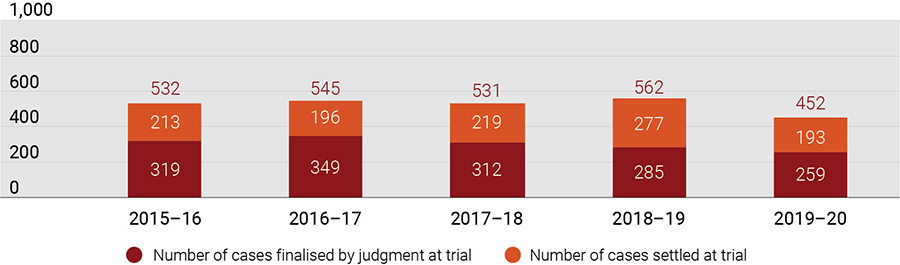

The Court’s cases are made up of complex matters that often involve multiple parenting or financial issues with high levels of conflict between the parties. This is reflected in the consistent percentage of cases proceeding to judgment. Figure 3.3 displays the five-year attrition and settlement trend in the Court’s caseload, and shows the stage reached by matters finalised in 2019–20, including the percentage that proceeded to judgment.

| Lodged | First Court Hearing/Conference | Pre-trial | Docket entry | Commence trial | Judgment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 100 | 78 | 46 | 37 | 27 | 14.1 |

| 2016-17 | 100 | 76 | 44 | 36 | 25 | 15.0 |

| 2017-18 | 100 | 77 | 46 | 39 | 25 | 16.0 |

| 2018-19 | 100 | 78 | 48 | 42 | 25 | 16.0 |

| 2019-20 | 100 | 79 | 49 | 43 | 25 | 16.2 |

First instance trials

Parties who are unable to settle their dispute require a judge to make a decision after a trial, although frequently parties reach an agreement during the trial process. Figure 3.4 provides the number of cases that are finalised at first instance trial.

Number of finalisations of all applications

During 2019–20, the Court finalised the following matters in its original jurisdiction:

- 2,394 final orders applications

- 3,216 applications in a case (interim)

- 14,946 consent orders applications, and

- 231 other orders applications (including Hague, contempt and contravention applications).

Each application type requires a different amount of Court resource effort to resolve. For example, final orders applications and associated interim applications require more judicial effort and registrar and family consultant involvement to resolve, whereas consent orders applications result from parties agreeing terms prior to filing and are considered by registrars.

The Court also deals with discrete applications, such as contravention and contempt applications, and applications made pursuant to the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction.

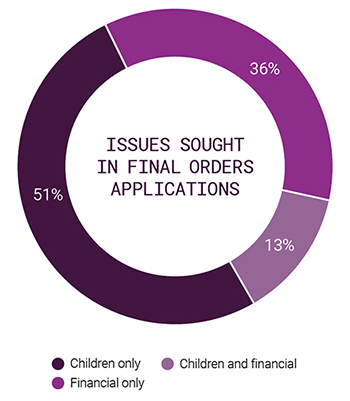

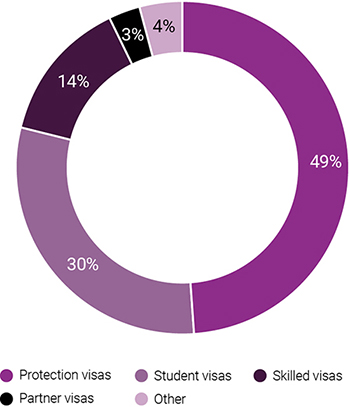

Final order applications

During 2019–20, 2,394 applications for final orders were finalised – one less than in 2018–19. The Court received an increased number of filings of applications for final orders in 2019–20 compared to 2018–19, an increase of 7.1 per cent. The majority of final order applications filed seek financial orders (49 per cent), followed by parenting orders (35 per cent) and both financial and parenting orders (14 per cent).

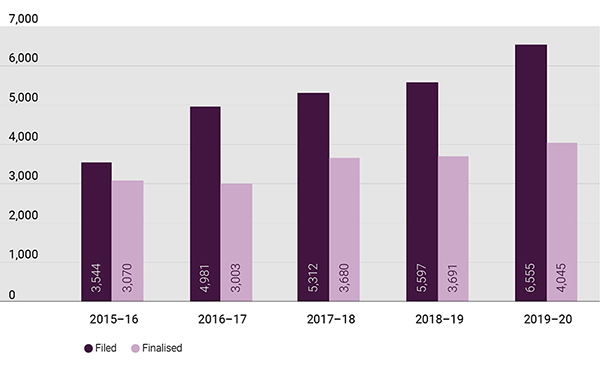

Figure 3.5 displays the five-year trend in filings, finalisations and pending (active) final orders applications. There is a continuing increase in the percentage of cases where there are allegations of child abuse or risk of child abuse, or family violence or risk of family violence involving a child or a member of the child’s family (see figures 3.18 and 3.19).

Applications in a case (interim applications)

Applications in a case (interim applications) are associated with an existing case. Often a party will file an application in a case seeking orders for interim parenting arrangements or interim financial arrangements, or procedural orders to facilitate the progression of the case. These orders may be sought on a urgent basis if there is an issue that requires the Court’s immediate attention. They can be complex and often there are multiple applications within one case. As shown in Figure 3.7, during 2019–20, 3,216 applications in a case were finalised, a slight increase from 2018–19.

Consent orders

During 2019–20, 14,946 consent orders applications were finalised – an increase of 865 (6.1 per cent) since 2018–19. These applications vary in complexity and are presented to the Court as an agreement between the parties. The applications are considered by a registrar, and where appropriate orders are made encompassing that agreement.

Figure 3.8 to Figure 3.10 display five-year trends in filings, finalisations and pending (active) applications.

Clearance rate

The Court aims to finalise at least the same number of cases that start in a year and, as such, aims to achieve a clearance rate of at least 100 per cent. A clearance rate of 100 per cent or higher indicates that the Court is reducing the backlog of pending cases.

In 2019–20, the Court achieved a clearance rate of 99 per cent for all application types and 101 per cent for final order applications. As stated above, it is likely that the Court would have achieved at least a 100 per cent clearance rate across all applications were it not for the impact of COVID-19. Figure 3.9 shows the five-year trend in the clearance rate for all applications.

Age of pending applications

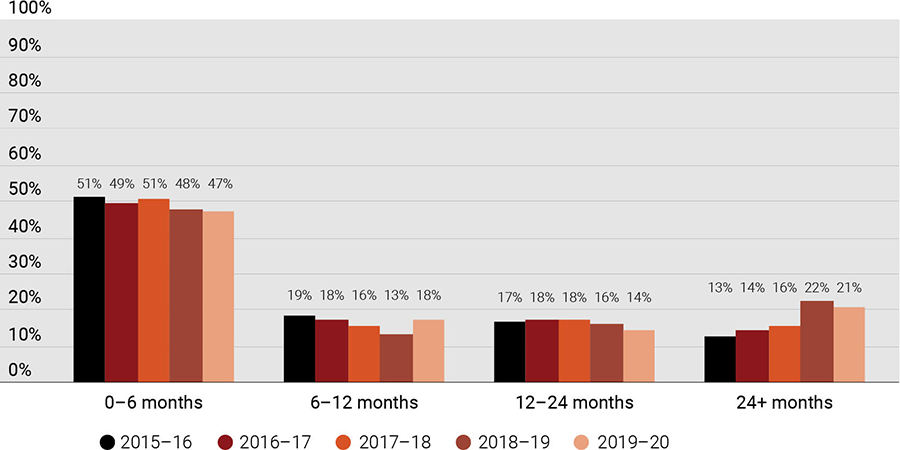

The Court aims to have more than 75 per cent of its pending applications less than 12 months old. At 30 June 2020, 65 per cent of pending applications were less than 12 months old, an improvement compared with 62 per cent at 30 June 2019.

The Court regularly reviews its oldest active cases to better understand the causes of their delay and to determine ways in which the older cases can be managed. In February and March 2020, the Court was undertaking the Summer Campaign to clear aging pending final order applications nationally across the Court through referrals to both internal and external ADR, including where appropriate, family dispute resolution (FDR) with both a registrar and family consultant. This was successful in resolving a number of matters, however the Summer Campaign was postponed after completion in only two registries due to COVID-19. Figure 3.10 and Figure 3.11 show the five-year trend in the age distribution of applications.

Age of finalised applications

The Court aims to finalise cases in a timely manner, noting the importance of family law decisions to the parties and their children, and the need to minimise the emotional and financial impact of family law litigation as far as possible. It is difficult to set and achieve a blanket timeliness target because the number of variables affecting the parties involved in each case has multiple impacts on its progress towards a decision. With this in mind, the Court aims to finalise 75 per cent of cases within 12 months. The other 25 per cent are the most complex cases, which may depend on factors outside the Court’s control such as the availability of expert reports or valuations, access to supervised contact centres, parenting courses or behavioural change programs, or other therapeutic interventions.

In 2019–20, of the cases finalised by the Court, about 93 per cent were finalised within 12 months. Figure 3.12 and Figure 3.13 show the five-year trend in the age distribution of applications finalised.

Age of reserved judgments delivered

The Court aims to deliver 75 per cent of reserved judgments within three months of completion of a trial. In 2019–20, 777 (83 per cent) of the 939 reserved original jurisdiction judgments (excluding judgments on appeal cases) were delivered within that timeframe. Information on the performance of the Appeal Division can be found in Part 4 (Appeals) of this report.

Figure 3.14 shows the five-year trend of reserved judgments delivered within three months and Figure 3.15 shows the breakdown of time to deliver reserved judgments.

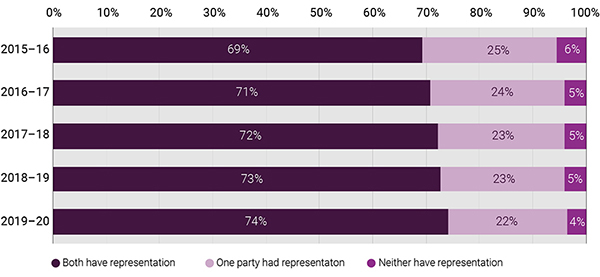

Unrepresented litigants

The Court monitors the proportion of unrepresented litigants as one measure of the complexity of its caseload. Unrepresented litigants present a layer of complexity because they need more assistance to navigate the Court system and require additional help and guidance to abide by the Family Law Rules and procedures.

Figure 3.16 shows litigants who had representation at some point in their proceedings. It is important to note that this graph does not describe the length of time for which a party retained legal representation. A litigant who was unrepresented from filing until the trial but engages legal representation at the trial stage is recorded the same as a litigant who had legal representation for the entirety of the proceeding. Figure 3.17 shows the proportion of litigants who had representation at the finalisation of their trial. There has been a small increase in matters involving one or both parties not having representation at some point in their proceedings, from 20 per cent in 2018–19 to 21 per cent in 2019–20. There has been a decrease in trials where both parties are unrepresented from 22 per cent in 2018–19 to 18 per cent in 2019–20.

Note: The Court has revised its counting rule for these figures and as such the values in this section differ from those published in previous reports. The figures now exclude cases that did not have a first Court event (i.e. withdrew or discontinued before appearing at Court) and so they had not proceeded beyond filing. The information about legal representation in these cases was often incomplete as the parties had not provided this information at the time of filing.

Family violence and abuse (or risk)

Section 67Z and s 67ZBA of the Family Law Act 1975 and Part 2.3 of the Family Law Rules 2004 require a Notice of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk of Family Violence to be filed in cases in which it is alleged that a child to a proceeding has been abused or is at risk of abuse, or where there is an allegation of family violence or risk of family violence involving a child or a member of the child’s family. Once filed, the notice must be sent to a prescribed child welfare authority.

The proportion of matters in which a Notice of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk of Family Violence has been filed does not reflect all the cases in which family violence is raised or is an issue. Allegations of abuse or risk of abuse and family violence or risk of family violence are also raised by parties in other ways; for example, in affidavits filed in the proceedings and by the filing of a Family Violence Order (Rule 2.05 Family Law Rules 2004).

Figure 3.18 shows that in 2019–20, the number of Notices of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk of Family Violence filed were sustained at a high level, indicating the complexity of the caseload before the Court. There is an upward trend in the number of Notices of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk of Family Violence filed each year, indicated by the trendline shown in Figure 3.18. This reflects the Court’s understanding of the prevalence of family violence in family law proceedings. It also reflects the growing awareness of family violence within the community and the need for litigants to raise family violence in conformity with the 2012 amendments. It also reflects the increasing complexity of the Court’s cases and the extent to which child abuse and/or family violence is an element in many of them.

Magellan cases

Magellan cases involve serious allegations of physical abuse and/or sexual abuse of a child and undergo special case management. When a Magellan case is identified, it is managed by a small team consisting of a judge, a registrar and a family consultant. Magellan case management relies on collaborative and highly coordinated processes and procedures. A crucial aspect is strong interagency coordination, in particular with state and territory child protection agencies. This ensures that problems are dealt with efficiently and that high-quality information is shared. An independent children’s lawyer is appointed in every Magellan case.

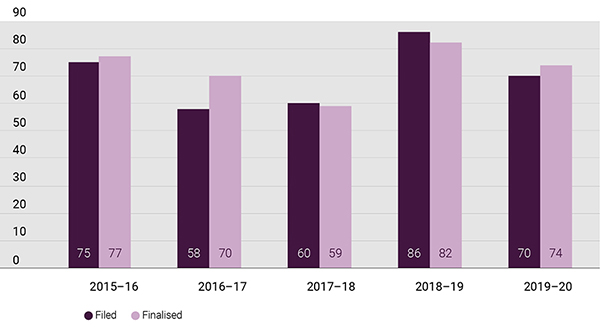

Typically, a Magellan case is one where a notice of abuse or family violence is filed, although not all notices will necessarily result in the case being classified as a Magellan matter. The Court assesses and determines, from the issues raised, the matters that are managed under the Magellan program. Figure 3.19 details the number of Magellan cases commenced and finalised in the past five years.

Complaints

Judges are accountable through the public nature of their work, the requirement that they give reasons for their decisions, and the scrutiny of their decisions on appeal.

Judicial services complaints are complaints about the conduct of judges or delays in the delivery of a judgment. These figures do not include complaints about registrars (these are included under ‘feedback and complaints management’ below). Complaints about judgments or orders can only be dealt with on appeal.

In 2019–20, the Court received 21 judicial services complaints, as follows:

- Judicial conduct – 4

- Delay in delivery of a judgment – 17

This represented 0.099 per cent of all applications filed (21,054), which is under the target of 1 per cent (when judicial complaints and administrative complaints are combined they total 0.163 per cent).

The number of judicial services complaints received by the Court in 2019–20 is shown in Figure 3.20, which also shows the breakdown between complaints about judicial conduct and complaints about delays.

Feedback and complaints management

The Family Court is committed to responding effectively to feedback and complaints. Comprehensive information about how to give feedback and lodge complaints is available on the Court’s website at www.familycourt.gov.au.

The judicial complaints procedure is also published on the website. That procedure is in line with the provisions inserted by the Courts Legislation Amendment (Judicial Complaints) Act 2012. It is also in line with the procedures of other federal courts.

The Court records all complaints made in relation to Family Court proceedings, although some complaints relate to services provided by the Federal Court, such as registry services or other third parties.

In this reporting year, the Court received the following complaints:

Complaints about Family Court services

Administrative processes – 5

Conduct of registrars – 3

Privacy – 2

Total – 10

Complaints arising from services provided by the Federal Court or other third parties and relating to Family Court matters

Conduct of administrative staff – 4

Conduct of family consultants – 7

Total – 11

These figures do not include complaints about judicial outcomes, which can be dealt with through the appeal process; matters that are in other courts, such as the Family Court of Western Australia; or complaints about family law legislation, which is a matter for the Government.

The total number of complaints regarding Family Court matters (11) represented 0.05 per cent of all applications received. Combined with judicial complaints (21), the total number of complaints (32) represented 0.163 per cent of applications received, thus achieving the key performance indicator for complaints to be no more than 1 per cent of applications received.

Initiatives in family law

COVID-19 List

The Family Court and the Federal Circuit Court have each established a Court list dedicated to dealing exclusively with urgent family law disputes that have arisen as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lists were established in response to an increase in the number of urgent applications filed in the Courts from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lists commenced on 29 April 2020.

The operation of the COVID-19 Lists is set out in Joint Practice Direction 3 of 2020: http://www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fcoaweb/rules-and-legislation/practice-directions/2020/jpd032020

The COVID-19 Lists are administered by the National COVID-19 List registrars. The national registrars consider the urgency of the applications filed and triage them to judges in each Court who have been assigned to the COVID-19 Lists. Applications that meet the COVID-19 criteria are given a first return date before a national registrar or a judge within three business days of being considered by the national registrar, or less if assessed as critically urgent.

The COVID-19 Lists operate electronically, meaning that the application may be heard by a judge from any registry. The COVID-19 List judge will hear the discrete COVID-19 application, or put interim arrangements in place to deal with the circumstances of urgency. Once that issue is dealt with, the remainder of the matter will be case managed by the docket judge or a registrar as appropriate.

From commencement of the Lists on 29 April 2020 to 30 June 2020, 214 applications for the COVID-19 List were received. All applications accepted into the Lists were given a first Court date within three business days.

National Arbitration List

Section 13E of the Family Law Act provides for the Court to refer Part VIII or Part VIIIAB proceedings, or aspects of those proceedings to arbitration. This can only be done with the consent of all parties. To support the development and promotion of arbitration for property matters in family law, in April 2020, the Family Court and the Federal Circuit Court each established a new specialist list – the National Arbitration List. Justice Wilson is the National Arbitration Judge for the Family Court.

The list operates as a national electronic list and includes the following features:

- whenever a matter is referred to arbitration that case will be placed into the National Arbitration List

- any application for interim orders sought by an arbitrator or one of the parties will be dealt with by the National Arbitration Judge electronically

- any applications relating to the registering of the arbitration award, objection to an award being registered or an application for review will be conducted by either the National Arbitration Judge or a nominated judge assigned by the Chief Justice or Chief Judge, and

- any appeal from a decision of the National Arbitration Judge or other nominated judge will be managed by Justice Strickland as the Coordinating Arbitration Appeal Division Judge.

Further information on the National Arbitration List can be found in the Information Notice The National Arbitration List available on the Court’s website at: http://www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fcoaweb/about/news/arbitration-list

Co-location of state and territory child welfare authorities and police

In early 2020, state and territory child welfare officials and police were co-located in the busiest family law registries of the Family Court and Federal Circuit Court as part of a co-location initiative announced by the Federal Government. The co-location initiative is intended to improve the sharing of information between the state and territory police and child welfare authorities and the family courts, and ensure that this information is available to judges and registrars at the earliest opportunity. It is anticipated that the co-location initiative will lead to a more cohesive response to identifying and managing family safety and child protection issues across the family law, family violence and child welfare systems.

Greater information sharing between agencies can provide a clearer picture of the nature, frequency and severity of violence or other risks to children occurring within a family and trigger earlier intervention or a more robust system response. It is anticipated that improved information sharing can improve the Courts’ ability to assess risk, triage and prioritise cases, and make orders which protect children and victims of family violence to the greatest extent possible.

The co-location of state and territory child welfare officials in the Courts’ family law registries follows the co-location of an officer from the Department of Health and Human Services in Victoria, which has operated successfully and proven a valuable resource for judges and registrars. The process has provided additional benefits including:

- early information for the triage of urgent cases

- reduction in the number of subpoenas and orders pursuant to section 91B of the Family Law Act 1975, and

- information flow between the Courts and the child welfare authority has improved the understanding within each entity of the other’s role.

Child welfare officials are co-located in most registries save for the Northern Territory. Police officials are co-located in most registries save for the Northern Territory and Victoria.

Information sought from co-located police officers may include information in relation to current or previous family violence orders, firearms licences, criminal convictions or pending criminal proceedings.

Harmonisation of the Family Law Rules 2004 and the Federal Circuit Court Rules 2001

The Courts are progressing the harmonisation of the Family Law Rules and the Federal Circuit Court Rules in so far as they apply in the family law jurisdiction of the Court, so as to create a single, harmonised set of rules. The Courts’ aim is to promote consistency of practice in the family law jurisdiction, and ensure as far as possible that there is a single set of rules that are clear and accessible for all users of the family law system. This is a project that has required the focus and dedication of judges and staff of both Courts, overseen by an independent Chair, the Honourable Dr Chris Jessup QC, and ably assisted by two barristers, Emma Poole and Chris Lum.

The Working Group’s efforts have produced a complete draft of the harmonised rules, which has been distributed to all judges for consultation, and will thereafter be distributed to the profession and other stakeholders for external consultation in the second half of 2020. While there is still some way to go before the rules, forms and case management practices across the Courts are harmonised, compiling a draft of the harmonised rules is a significant achievement which had not been able to be accomplished in the past 20 years.