Report on court performance

The stated outcome of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (Federal Circuit Court) is:

Apply and uphold the rule of law for litigants in the Federal Circuit Court of Australia through more informal and streamlined resolution of family law and general federal law matters according to law, through the encouragement of appropriate dispute resolution processes and through the effective management of the administrative affairs of the Court.

The Court has the following targets under performance measures of timely completion of cases and timely registry services:

Timely completion of cases

- 90 per cent of final orders applications disposed of within 12 months

- 90 per cent of all other applications disposed of within six months, and

- 70 per cent of matters resolved prior to trial.

Timely registry services

- 75 per cent of counter enquiries served within 20 minutes

- 80 per cent of National Enquiry Centre (NEC) telephone enquiries answered within 90 seconds

- 80 per cent of email enquiries responded to within two working days, and

- 75 per cent of applications lodged processed within two working days.

Snapshot of performance

| TIMELY COMPLETION OF CASES | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Target |

Result 2018–19 |

Target status |

|

90 per cent of final orders applications disposed of within 12 months |

62 per cent of final orders applications were disposed of within 12 months |

Target not met |

|

90 per cent of all other applications disposed of within six months |

92 per cent of all other applications were disposed of within six months |

Target met |

|

70 per cent of matters resolved prior to trial |

72 per cent of matters were resolved prior to trial |

Target met |

| TIMELY REGISTRY SERVICES | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Target |

Result 2018–19 |

Target status |

|

75 per cent of counter enquiries served within 20 minutes |

90 per cent of counter enquiries were served within 20 minutes |

Target met |

|

80 per cent of NEC telephone enquiries answered within 90 seconds |

10 per cent of NEC telephone enquiries were answered within 90 seconds |

Target not met |

|

80 per cent of email enquiries responded to within two working days |

100 per cent of email enquiries were responded to within two working days |

Target met |

|

75 per cent of applications lodged processed within two working days |

98 per cent of applications lodged were processed within two working days |

Target met |

Workload in 2018–19

|

Family law |

Total |

% of total |

|---|---|---|

|

Divorce orders |

44,342 |

47% |

|

Interim orders |

22,115 |

23% |

|

Final orders |

17,070 |

18% |

|

Other applications |

1707 |

2% |

|

Total family law |

85,234 |

90% |

|

General federal law |

Total |

% of total |

|---|---|---|

|

Migration |

5591 |

5% |

|

Bankruptcy |

2885 |

3% |

|

Other |

2220 |

2% |

|

Total general federal law |

10,096 |

10% |

|

Grand total |

95,330 |

100% |

Case management

The Federal Circuit Court uses a docket case management process designed to deal with applications in a flexible and timely way. The docket case management process has the following principles:

- matters are randomly allocated to a judge who generally manages the matter from commencement to disposition; this includes making orders about the way in which the matter should be managed or prepared for hearing, and

- matters in areas of law requiring expertise in a particular area of jurisdiction are allocated to a judge who is a member of the relevant specialist panel.

The docket case management system provides the following benefits:

- consistency of approach throughout the matter’s history

- the judge’s familiarity with the matter results in more efficient management of the matter

- fewer formal directions and a reduction in the number of court appearances

- timely identification of matters suitable for dispute resolution, and

- allows issues to be identified quickly and promotes earlier settlement of matters.

Specialist panel arrangements

The Court has specialist panels in areas of general federal law and child support which ensure that matters of a specialist legal nature are allocated to judges with expertise in that particular area of the Court’s jurisdiction.

Specialist panel members meet regularly with user groups and judicial colleagues from other courts to respond to issues of practice and procedure in these specialist jurisdictions.

The following panels support the work of the Court:

- commercial (including consumer,intellectual property and bankruptcy)

- migration and administrative law

- human rights

- industrial law

- national security

- admiralty law, and

- child support.

The panel arrangements equip the Court with the ability to effectively utilise judicial resources in specialist areas of family and general federal law. They are an essential element of continuing judicial education within the Federal Circuit Court.

Report on work in family law

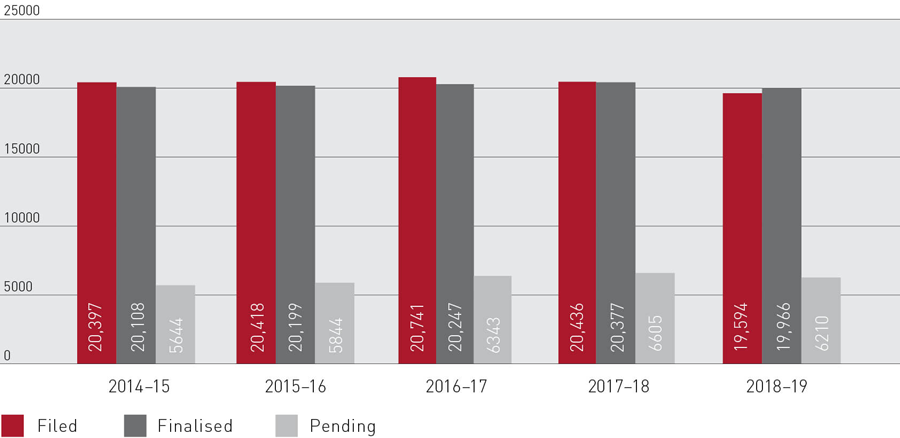

Family law constitutes the largest proportion of the overall workload of the Court, representing 89 per cent of all family law work filed at the federal level. This compares with 87 per cent during 2017–18.

|

Application |

Filed |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Divorce applications |

44,342 |

52% |

|

Interim applications |

22,115 |

26% |

|

Final orders applications |

17,070 |

20% |

|

Other applications |

1707 |

2% |

|

Total |

85,234 |

100% |

Due to rounding, percentages may not always appear to add up to 100%.

Final orders applications are filed when litigants seek to obtain final parenting and/or financial orders. Applications in a case (interim) seek interim or procedural orders pending the determination of final orders.

The family law workload (excluding divorce) can be broken into three main categories. In 2018–19, 51 per cent of family law applications related specifically to matters concerning children, a further 13 per cent involved both children and property, and 36 per cent involved discrete property applications.

Divorce

The Federal Circuit Court deals with all divorce applications filed (other than in Western Australia) and the work is largely undertaken by registrars. A divorce application only proceeds to a judge for determination if it is contested. Many applications are made by unrepresented litigants with the assistance and information in the form of online guides that allow them to navigate the procedural requirements.

In addition, in some localities, staff from the Court Network are available to support litigants as it is appreciated that for many litigants a court appearance can be stressful and unfamiliar.

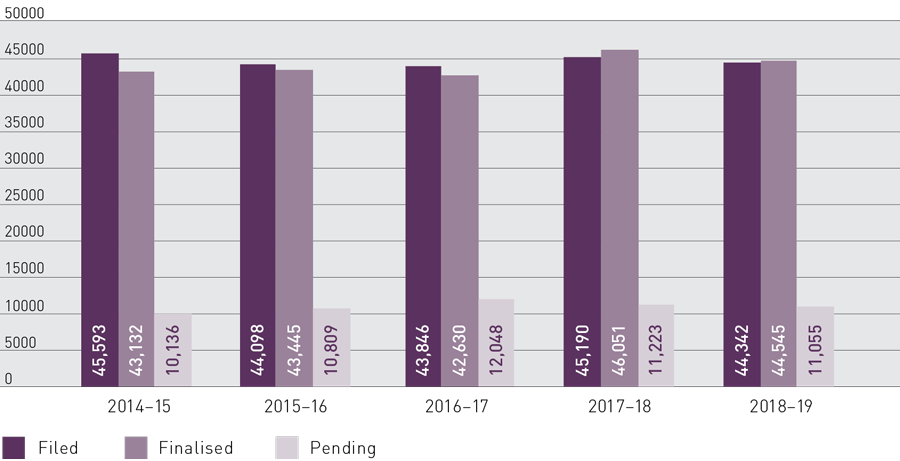

During the year, 44,342 divorce applications were filed in the Court. This compares with 45,190 in 2017–18.

A significant number of calls to the NEC relate to divorce proceedings, in particular providing information to assist eFiling on the Commonwealth Courts Portal (the Portal) and directing litigants to the website to complete the divorce checklist at How do I apply for a divorce?

The dynamic interactive checklist was created to assist litigants when applying for a divorce so there is less chance of errors in applications. The NEC also provides general divorce support in relation to applying, service and information about court events, as well as administrative support for Portal users and assisting litigants and lawyers when they register and eFile applications for divorce.

The Court has also developed a fully electronic divorce file which permits the management of divorce applications in electronic format from filing to disposition. These initiatives meet a range of objectives including aligning with federal government strategies for digital administration and records management, and offering litigants and the legal profession streamlined services. The Court still accepts hard copy applications from litigants, lawyers and others who do not have access to technology and converts them to a digital record.

In 2018–19, over 80 per cent of all divorce applications were eFiled, with this percentage expected to grow as enhancements are made to the process. Litigants and practitioners are being encouraged to eFile divorce applications in view of the benefit to litigants. One such benefit is the ability to select from a list of available hearing dates. There are also administrative benefits for registries not only in the reduction of hard copy files and accompanying storage, but also greater flexibility in the management of the divorce workload.

Brochures have been developed to assist those who may not be able to eFile their applications to seek assistance through a community legal centre. Public access computers are available in all registries and have been equipped with access to the Portal so that litigants can upload documents at registry locations. In addition, the website information has been revised to better assist litigants applying for a divorce. New features include interactive steps to assist applicants to better understand the legal requirements.

Even if paper applications are received, registry staff scan and upload the documents on the case management system. This ensures Portal access to all the documents on the divorce file (whether filed electronically or manually at the registry). Since 1 January 2018, divorce orders are no longer posted. NEC staff register and link clients to their file on the Portal via phone, live chat or email (registerme@comcourts.gov.au).

Child support

The Court exercises some limited first instance and appellate child support jurisdiction. The child support review framework has proceeded from a court-based process to one that is now predominantly administrative.

Following the merger of the Social Security Appeals Tribunal, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) now hears appeals from most decisions of the Child Support Registrar. Appeals to the Court are accordingly limited to appeals on a question of law from decisions of the AAT.

While the Court shares this review jurisdiction with the Federal Court, most appeals proceed before the Federal Circuit Court and are few in number. This is reflected in the number of child support appeals for the year, which was 22 – three less than were filed in the previous year.

A significant proportion of the enforcement workload of the Court is in relation to applications for enforcement of child support arrears. To facilitate this, discrete child support enforcement lists have been set up in the larger registries as an effective means of dealing with this workload.

Report on work in general federal law

|

General federal law |

Total |

% of total |

|---|---|---|

|

Administrative law |

53 |

0.52% |

|

Admiralty law |

6 |

0.06% |

|

Bankruptcy |

2885 |

28.58% |

|

Intellectual property |

43 |

0.43% |

|

Human rights |

86 |

0.85% |

|

Industrial |

1291 |

12.78% |

|

Migration |

5591 |

55.38% |

|

Consumer law |

141 |

1.40% |

|

Total |

10,096 |

100% |

Due to rounding, percentages may not always appear to add up to 100%.

Administrative

The Court has original jurisdiction under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977.

The Court’s AAT review jurisdiction is generally confined to matters remitted from the Federal Court and excludes those appeals from decisions of the AAT constituted by a presidential member. However, in respect of judicial review of migration and child support first review, the jurisdiction of the Court is not subject to remittal.

As noted in previous annual reports, the Court considers there is scope for expanding the jurisdiction of the Court to encompass some review rights under s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903.

Excluding those judicial review applications filed in respect of migration, the number of administrative review matters that proceed before the Court are few in number (53 in 2018–19).

Admiralty

Although the number of applications in person filed under this head of jurisdiction is small (6 in 2018–19), it is an important jurisdiction conferred under s 76 (iii) of the Constitution. The admiralty and maritime jurisdiction conferred on this Court is a dispute subject matter that requires an appreciation and understanding of the United Nations Law of the Sea Conventions and the domestic legislation giving effect to maritime-related international treaties and conventions.

The work is undertaken by a discrete panel of judges who are required to maintain appropriate breadth of knowledge in admiralty and maritime law.

The jurisdiction of the Court is governed by the Admiralty Act 1988. Section 9 of that Act confers in personam jurisdiction on the Court for matters falling within the meaning of a maritime claim as defined in s 4. While confined to in personam disputes, the Court can also hear in rem matters referred to it by the Federal Court, which is not limited by quantum.

As proceedings commenced in personam in the Court can be transferred to the Federal Court, the Federal Circuit Court is a convenient forum for preserving time limitations in disputes concerning carriage of goods, charter parties, collisions, general average and salvage. The jurisdiction in personam is not limited by quantum.

The Act applies to all ships irrespective of domicile or residence of owners and to all maritime claims wherever arising. The admiralty rules set out standard procedures supplemented by the Rules of Court, and the Admiralty Rules 1988 (Rule 6).

In previous annual reports, the issues of enforcement of foreign judgments has been highlighted as an issue of concern to the Court, as much depends upon general principles of reciprocity. Not being a superior court, the ability of the Court to transfer where issues of enforcement arise is a useful power.

The new Admiralty and Maritime Practice Direction, issued by the Chief Judge on 3 June 2019, has revitalised this important area of the Court’s general federal jurisdiction. See http://www.federalcircuitcourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fccweb/rules-and-legislation/information-notices/admiralty-law/admiralty_notice2019.

The unlimited general federal jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit Court in the in personam matters conferred by the Admiralty Act 1988 is of great utility for litigants involved in maritime commerce disputes and their legal practitioners. The Court can also exercise jurisdiction in respect of matters remitted by the Federal Court.

The lower court costs and now streamlined and unified procedures for case management of these maritime matters, will simplify and make more accessible resolution of the in personam maritime disputes. The Court can readily accommodate interstate appearances by legal practitioners at the case management hearings by either telephone or video link and can make orders to facilitate the same.

While the numbers of maritime matters at this stage filed in this court are not substantial, there is considerable importance in facilitating the fair, inexpensive and expeditious determination of maritime disputes.

The new case management procedures will still ensure that maritime matters ready for final hearing are promptly heard and determined by judges of the Court in the local registries where the matters are filed, except where exigencies within the Court require otherwise. The judges of the Court deal with a vast range of general federal law matters and the Court will continue to expand and enhance access to justice in this special area of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction.

Bankruptcy

The Court shares personal insolvency jurisdiction with the Federal Court, most of which proceed in the Federal Circuit Court. The Court does not have any jurisdiction in respect of corporate insolvency.

A significant proportion of bankruptcy matters are case managed and determined by registrars. This includes:

- creditors’ petitions

- applications to set aside bankruptcy notices, and

- examinations pursuant to s 81 of the Bankruptcy Act.

The Court appreciates the significant work undertaken by registrars who exercise extensive delegations in respect of the bankruptcy jurisdiction.

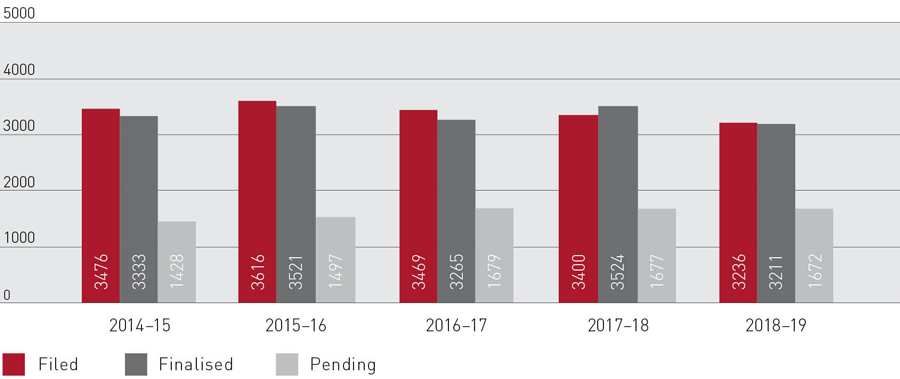

The Court received 2885 bankruptcy applications in 2018–19, and finalised 2823. This represents a decrease in bankruptcy filings of six per cent, compared with 3072 filings in 2017–18.

In light of the shared personal bankruptcy jurisdiction, the Federal Court and the Federal Circuit Court have adopted harmonised bankruptcy rules:

- Federal Circuit Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016, and

- Federal Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016.

The Bankruptcy Amendment (Debt Agreement Reform) Act 2018 amended the Bankruptcy Act 1966 to effect a comprehensive reform of Australia’s debt agreement system. The majority of the amendments commenced on 27 June 2019.

The reforms include changes to:

- the length of a debt agreement a debtor can propose debtor eligibility to enter into a debt agreement

- the official receiver’s powers to refuse to accept a debt agreement proposal in exceptional circumstances

- creditor voting rules around debt agreements

- debt agreement administrator registration requirements, and

- the Inspector-General’s investigation and inquiry powers.

Representatives from the courts meet regularly with officers from the Australian Financial Security Authority on current issues and trends in relation to personal insolvency law and procedures.

Consumer

The consumer law jurisdiction of the Court is confined and there is a monetary limit on the grant of injunctive relief and damages up to $750,000. The number of filings under this head of jurisdiction is accordingly small (141 in 2018–19).

Consumer law now has a national framework following the commencement, on 1 January 2011, of the Australian Consumer Law. This cooperative framework is administered and enforced jointly by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and the state and territory consumer protection agencies.

The regulatory framework surrounding consumer protection, in the context of the banking, insurance and financial services sectors, has been the subject of some oversight. On 29 November 2016, the Senate referred an inquiry into the regulatory framework for the protection of consumers, including small businesses, in the banking, insurance and financial services sector (including managed investment schemes) to the Senate Economics References Committee for inquiry and report.

In November 2018, the committee provided its report and recommended that the Federal Government consider increased funding for community legal and financial counselling services dealing with victims of financial misconduct.

Additionally, the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry was established on 14 December 2017. The Commissioner, the Honourable Kenneth Madison Hayne AC QC, provided his final report on 1 February 2019.

Human rights

The Australian Human Rights Commission has statutory responsibilities under the following laws to investigate and conciliate complaints of alleged discrimination:

- Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986

- Age Discrimination Act 2004

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992

- Racial Discrimination Act 1975, and

- Sex Discrimination Act 1984.

The Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986, formerly the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act 1986, establishes the statutory framework for making complaints of unlawful discrimination.

Once a complaint of unlawful discrimination is terminated, a person affected may make an application to the Federal Court or Federal Circuit Court alleging unlawful discrimination by one or more respondents to the terminated complaint.

The number of matters that proceed to the Court is relatively small. In 2018–19 there were 86 applications filed under this head of jurisdiction.

There is generally an overlap of Commonwealth and state/territory laws that prohibit the same type of discrimination. For example, the Fair Work Act 2009 also deals with discrimination, harassment and bullying, in the context of the workplace.

The following are some of the types of matters that came before the Court under this head of jurisdiction during the year.

- In Eastman v Shamrock Consultancy Pty Ltd [2018] FCCA 3436, the applicant was dismissed from her employment because of her medical condition. The applicant subsequently filed an application with the Fair Work Commission (FWC) alleging dismissal in contravention of the general protections provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009. After the FWC proceedings failed to settle at conciliation, the applicant discontinued there and filed a complaint with the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) alleging disability discrimination and a failure to make reasonable adjustments for her.

In the first decision on what was then relatively new legislation, the applicant sought leave to commence proceedings pursuant to s 46PO(3A) of the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (AHRC Act). This provides that an applicant requires leave to bring such proceedings in the Federal Court or the Federal Circuit Court, unless the President of the Commission terminated the complaint (a) because he or she was satisfied that the subject matter of the complaint involved a significant issue of public importance that should be considered by the courts or (b) was satisfied that there was no reasonable prospect of the matter being settled by conciliation. The Court in the judgment considered the breadth and limits of the discretion in s 46PO(3A) of the AHRC Act, finding that it was unfettered subject to the subject matter, scope and purpose of the AHRC Act and that justice and equity were the touchstones for its exercise. It was held that in considering the justice and equity of the situation, one of the matters to take into account will be whether the proposed application for substantive relief has a reasonable prospect of success.

- In Prins v News Corp Australia Pty Ltd and Ors [2018] FCCA 3597, the applicant commenced proceedings seeking compensation for breaches of s 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). During the course of a public debate as to whether s 18C of the Act required amendment, the applicant complained that respondents sent her emails and published an article because of her race or ethnic origin. In a strike out application brought by the respondents, it was held that the evidence did not indicate any causal connection between the respondent’s conduct in sending the emails and publishing the article on the one hand, and the applicant’s race or ethnic origin on the other. The Court found that the applicant had no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting her proceedings against any of the respondents and that it should be summarily dismissed.

- In Hill v Hughes [2019] FCCA 1267, the Court found that the respondent who was a solicitor had engaged in relentless and unwanted conduct of a sexual nature towards the applicant who was his employee constituting sexual harassment under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth). In the circumstances of this case, the Court awarded the applicant $120,000 in general damages and separately awarded the applicant aggravated damages in the sum of $50,000. The grounds for the award for aggravated damages were:

– the threat that the respondent made to the applicant to stop her from making a complaint

– the lies told by the respondent in the litigation, and

– the use of privileged information gleaned while acting as the applicant’s legal representative for the sole purpose of blackening the applicant’s name in the proceedings.

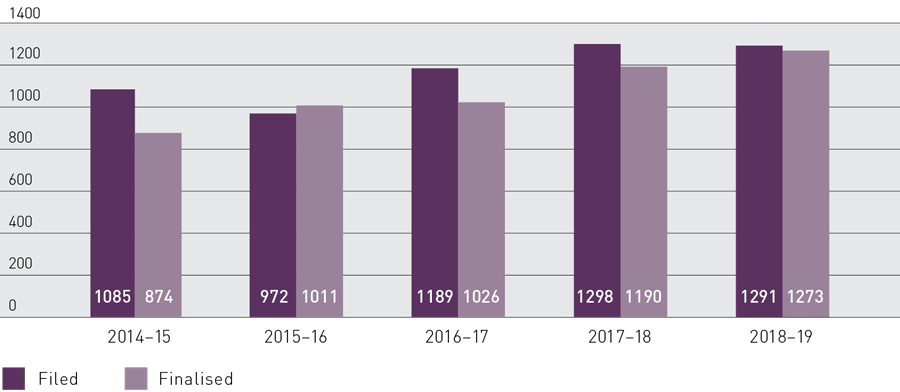

Industrial

Since the conferral of industrial law jurisdiction on the Court, the workload under this head of jurisdiction has grown. The Court has jurisdiction to deal with a broad range of matters under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the FW Act) and the last year has not seen a further increase in the number of applications for penalties and compensation as a result of alleged breaches of the FW Act.

Legislative developments have included amendments to the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 by way of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment Act 2016, which included the conferral of jurisdiction on the Federal Circuit Court to impose civil remedies against persons taking action against whistle blowers by way of reprisal action (as defined).

Migrant Workers’ Taskforce Report

The Migrant Workers’ Taskforce Final Report was released on 7 March 2019. The taskforce was established on 4 October 2016 and was preceded by a significant number of high profile cases revealing exploitation of migrant workers. For more information about the taskforce, see Initiatives in general federal law on page 49.

Significant decisions

During the reporting year, there have also been a number of significant decisions:

- In Fair Work Ombudsman v ZNZ Education Pty Ltd [2018] FCCA 3136, during a penalty hearing for orders pursuant to section 545(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), the applicant sought that the Court make ‘education orders’ requiring those who had contravened provisions of the Act to carry out a form of education which would relevantly inform them of their employment responsibilities. It was held that s 545(1) of the FW Act does not permit the Court to make penal ‘education orders’ in respect of past contraventions.

- In Ridd v James Cook University [2019] FCCA 997, the Court had to consider the rights of an employee to issues such as freedom of speech and intellectual freedom. The applicant, Professor Ridd, had publicly criticised a colleague and a related body to the University on a number of studies on the effect of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef. The University censured the applicant for breaching the Code of Conduct and directed him to keep the matter confidential and also gave a direction as to how he was to conduct himself in the future. After allegedly further breaches of directions, breaching confidentiality directions and breaches of the University’s Code of Conduct, the Vice-Chancellor terminated the applicant’s employment. It was held that the applicant had the rights to intellectual freedom afforded to him under clause 14 Enterprise Agreement (EA). The Code of Conduct was subordinate to

- the EA and hence the applicant’s termination was unlawful.

- In Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v BGC POS Pty Ltd & Anor [2018] FCCA 1270, the Court considered the circumstances in which an occupier will be considered to have intentionally hindered and obstructed a permit holder who holds an entry permit under the FW Act, by failing to agree to a request to use the default location for the purposes of holding discussions under s 484 of the FW Act. The decision also considers whether ignorance of the law is a defence to the contravention of s 502 of FW Act. The decision highlights how critical it is for front line managers to be properly trained in managing right of entry requests. The Court found that a failure to comply with a lawful request, even for a very short period, can result in a finding that the person has contravened the FW Act and will expose them (and their employer) to potential disputes and penalties. An appeal was dismissed (in February 2019) in BGC POS Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining & Energy Union [2019] FCA 74.

- In Fair Work Ombudsman v OzKorea Pty Ltd & Ors [2018] FCCA 2350, the Court considered the principles involved in determining accessory liability and whether a party had knowledge of the essential elements of facts going to contravention.

Finally, the Court’s small claims jurisdiction continues to provide a ready means by which employees can, through the less formal process in s 548, secure orders for payments of their lawful entitlements under the FW Act.

Intellectual property

The intellectual property (IP) jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit Court comprises proceedings arising under copyright, design and trade marks Commonwealth statutes. In its associated jurisdiction, the Court’s jurisdiction includes any proceeding for the tort of passing off or any analogous claim for false or misleading conduct under the Australian Consumer Law. With the exception of patents and circuits layouts, the Court’s jurisdiction is largely concurrent with that of the Federal Court.

The IP work of the Court is undertaken by a discrete panel of judges within the Court’s specialist National Practice Areas in general federal law who are required to maintain an appropriate breadth and depth of knowledge in copyright, design and trade marks law, passing off and analogous claims.

From 1 July 2019, the Federal Circuit Court will commence the National IP list to better promote the Court as a forum for IP litigation. The National IP list extends the IP pilot conducted in the Court’s Melbourne registry since 30 June 2017, to streamline the management of IP matters. Supporting the Court’s National IP initiative, Judge Baird will be the judge in charge of the IP National Practice Area. All IP matters filed in the Court are to be docketed to Judge Baird, who will case manage the matters through the interlocutory steps and to hearing.

Through the National IP list, the Court seeks to provide consistency in case management and interlocutory processes, to identify matters requiring early hearing dates, and to encourage early identification and narrowing of issues in dispute. Improving convenience and obviating the costs of in-person attendance, through the National IP list, the Court undertakes case management hearings on the papers, by telephone and by video link with multiple registries, and electronic case management. The Court encourages the use of alternative dispute resolution for the resolution of IP litigation, including through the Court’s mediator registrars (who hold dual appointments with the Federal Court).

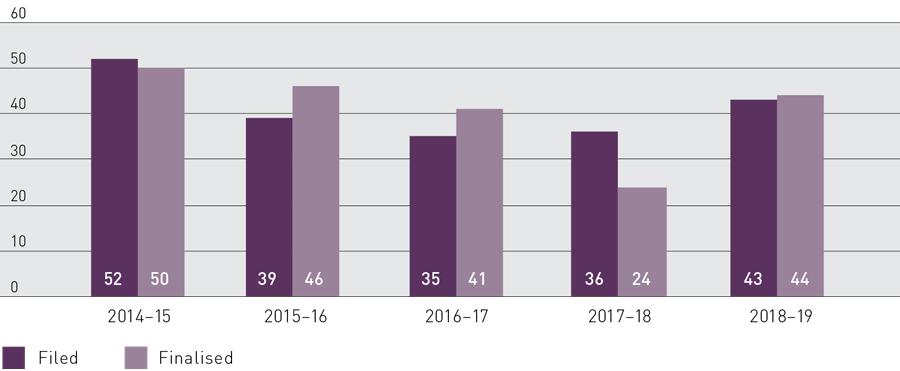

[Note, the figures for 2016–17 have been adjusted from the 2017–18 Annual Report, with more accurate inputs]

Guiding the conduct of IP matters in the Federal Circuit Court, the IP Practice Direction, Practice Direction No. 1 of 2018, applies nationally with respect to all IP proceedings commenced in the Federal Circuit Court after 1 July 2018. See http://www.federalcircuitcourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fccweb/gfl/intellectual-property/pd/.

There was extensive consultation with stakeholders prior to the commencement of the Melbourne IP pilot, and Judge Baird continued that engagement with the IP profession through 2018–19.

As stated in previous annual reports, historically the IP jurisdiction of the Court has been underutilised. The Court is well placed to hear and determine IP disputes, especially straightforward and less complex cases (one to three day hearings) and appeals from the offices of IP Australia, in a cost effective and streamlined way. The Court offers a simple, accessible and less expensive alternative to IP litigation, particularly attractive to individual rights-holders and small and medium enterprises.

Establishing an effective framework for enforcement of IP rights was the subject of consideration by the Productivity Commission inquiry into IP arrangements in Australia. Recommendation 19.2 highlighted the Federal Circuit Court as a possible forum for enforcement where IP rights are being infringed or are threatened. Included in Recommendation 19.2 of the report, released by the Productivity Commission, was the extension of this jurisdiction to ‘…hear all IP matters…’, which would include patent disputes. This recommendation went on to state: ‘The Federal Circuit Court should be adequately resourced to ensure that any increase in its workload arising from these reforms does not result in longer resolution times’. See www.communications.gov.au/departmental-news/release-productivity-commissions-intellectual-property-report.

With the conduct of the National IP list, the number and diversity of filings in IP matters in the Federal Circuit Court has increased. It is a small, but an important and growing part of the Court’s jurisdiction and work.

Examples of the types of IP proceedings that have proceeded before the Court during the year include appeals (hearings de novo) from decisions of the Registrar of Trade Marks (Office of IP Australia), infringement of registered design – damages claims, infringement of copyright works and other subject matter (cinematograph films, sound recordings), breach of copyright licences and infringement of copyright in sound recordings, and infringement of trade marks, and trade mark infringement proceedings following Customs seizures of goods.

The following are examples of IP judgments and proceedings before the Court during the year:

- In Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Pty Ltd & Ors v Hairy Little Sista Pty Ltd & Anor [2018] FCCA 2794, the copyright owners and PPCA, on behalf of its licensees, sought injunctions and damages from the respondents who operated bars/restaurants. The applicants sought orders restraining the respondents from playing protected sound recordings by the Beatles, Blue Swede and seven others without a licence. The Court found that the respondents had infringed copyright, having ignored nearly 40 attempts to be contacted. As such, the Court made declarations as to the breaches of copyright and ordered the respondent pay in the order $35,000 compensatory damages and $150,000 additional damages pursuant to s 115(4) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) plus interest and costs.

- In Google LLC v Weeks [2018] FCCA 3150 the Court heard an application for summary judgment seeking quia timet relief for infringement of the applicant’s well known trade marks, and restraining the respondent from using any of the names ‘Google LLC’ and ‘Google Legacy’ which he had registered under the Business Names Registration Act 2011 (Cth), domain name, and contravening s 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law, and for passing off. On application by the applicant, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) had declined to deregister the respondent’s business names. The respondent did not participate in the proceeding. The Court allowed substituted service and made interlocutory orders. On hearing of the summary judgment application, the Court considered relevant Business Names Registration Act provisions and evidence of the respondent’s recent activity on Facebook accounts and websites and was satisfied that quia timet relief ought be granted. The Court made orders restraining the respondent from infringing the applicant’s trade marks and using the names, and orders resulting in the cancellation or deregistration of the above business names.

- In Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc & Anor v Jeremy Taylor [SYG 1205 of 2018], the Court considered whether, by modifying software, the circumvention of technological protection measures was an infringement of copyright and breached user licence agreement. In the course of case management, the parties agreed to undertakings and orders. The Court was satisfied that it was appropriate to make declarations and orders permanently restraining the respondent from infringing copyright in the applicant’s source code embodied in a video game and its multiplayer feature software.

- In Nike Innovate C.V. & Ors v Li Hong Li & Ors [MLG 2281 of 2018], the applicants sought injunctions restraining the respondents from infringing the applicant’s trade marks. The infringements occurred by the respondents selling counterfeit merchandise from market stalls. Over the course of case management hearings, the Court approved consent orders that the first six respondents be restrained from infringing the applicants’ trade marks and requiring them to make affidavits concerning the identity of the supplier of the counterfeit goods. The supplier was then joined as a respondent. The matter was resolved by consent orders requiring the supplier to pay damages, costs and/or an account of profits, as well as restraining the supplier from infringing the applicants’ trade marks.

Migration

As reported in previous annual reports, the Court has expected a significant upward trend in the migration workload as a result of increasing numbers of reviews by the Independent Assessment Authority of the ‘asylum legacy caseload’ which comprises asylum seekers who arrived unauthorised by boat between August 2012 and December 2013 and were not transferred to an offshore processing centre.

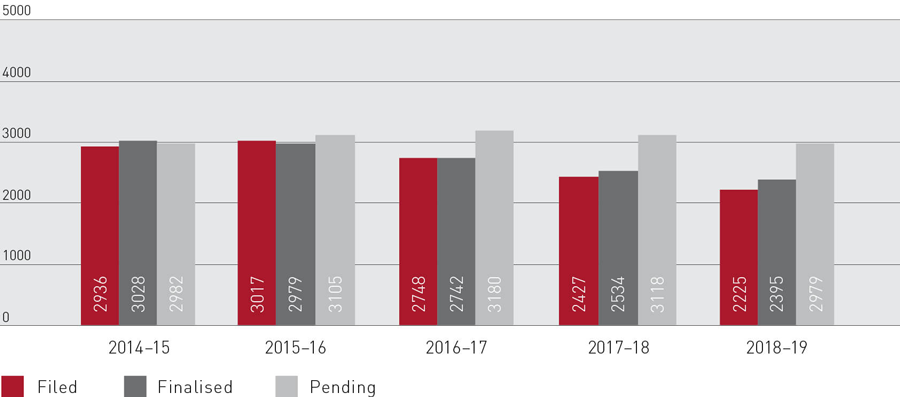

As is apparent in Figure 3.12, there has been a significant increase (5 per cent) in the migration workload during the reporting period. Migration represents the largest jurisdiction in the Court’s general federal law defended hearing list.

The increase is placing pressure on judicial resources. The early identification of matters that may have implications for a wider cohort, particularly those relating to the ‘fast track caseload’, could assist the Court. Efforts are being made for the early identification of such matters. Matters where litigants are in detention are similarly identified.

Although the Court is able to utilise the assistance of registrars at the direction stage, the nature of the jurisdiction is such that most applications require the allocation of judicial hearing and writing time. The Court is mindful of the impact delays may have on matters proceeding expeditiously where there are substantive issues of law to be resolved.

During the year, the Court continued the consultation with stakeholders to explore ways in which to facilitate the timely disposition of the migration workload. The feedback highlighted the need for provision of adequate judicial and other resources as being essential to the timely resolution of the migration caseload. In addition, there was seen to be a need for greater consistency in listing practices with suggestions for streamlining procedures and standardising directions and orders.

Migration law can be seen as a specialist area of administrative law that is often the subject of constitutional challenge. The jurisdiction exercised by the Court is judicial review based on statutory interpretation and case law.

Following are some examples of the types of migration proceedings that have proceeded before the Court during the year:

- In AFD17 v Minister for Immigration & Anor [2018] FCCA 1376, a critical fact in this case was whether the applicant had inherited the position of Malik from his grandfather. While acknowledging country information indicated Maliks were at some risk of being targeted for serious harm in Pakistan, the AAT did not accept on the evidence before it that the applicant was a Malik as claimed. The applicant had provided a letter from a member of the Pakistani National Assembly who represented the applicant’s home area that stated that he had personally conferred the status of Malik on the applicant. The applicant asked the Tribunal to contact the MP, however it failed to do so. It was held that while the Tribunal was not bound by the Migration Act to call the MP, in the circumstance of this case, it should have done so and so its decision was affected by jurisdictional error.

- BDI17 v Minister for Immigration & Anor [2018] FCCA 2162, was a case where the Immigration Assessment Authority decided to refuse an applicant’s application for a protection visa where he claimed fear of harm in Sri Lanka and where he was disbelieved in critical respects. It was held that the authority’s failure to get an updated Department of Foreign Affairs country report lacked any evident and intelligible justification and so was legally unreasonable. The decision of the authority was affected by jurisdictional error.

- Erasga v Minister for Immigration & Anor [2019] 228, involved the review of the refusal by the AAT of a partner visa. The Tribunal in its first decision was not satisfied that the visa applicant and his sponsor were in a genuine de facto relationship. After the Tribunal made its first decision, it was made aware that there had been evidence before it at the time of that decision that had not been taken into account. The Tribunal re-opened the review based upon an asserted jurisdictional error. The Tribunal then conducted another hearing in which new adverse material was put to the applicant. The Court considered whether the actions of the Tribunal in relation to the re-opening of the review in its second decision established an apprehension of bias. The Court held that the actions of the Tribunal were reasonable and that the second decision was not affected by any jurisdictional error.

- In CAK16 v Minister for Immigration (2018) 338 FLR 31; [2018] FCCA 2670, the Court quashed the decision of the AAT on the basis that defects and irregularities by the interpreter meant that the Tribunal had not provided the applicant with a fair hearing. The decision was upheld on appeal, see Minister for Home Affairs v CAK16 [2019] FCA 322.

- In Pham v Minister for Immigration (2018) 337 FLR 378; [2018] FCCA 2522, the Court quashed the decision of the AAT on the basis that due to a technical difficulties, part of the hearing before the Tribunal was not recorded and so for that part there was no transcript. Adverse findings on credibility were made by the Tribunal against the first and second applicants. It was held that the Court was not able to have comfort in being able to assess the short reasons of the Tribunal by reference to the transcript and so the proceeding before the Tribunal miscarried.

- In Singh v Minister for Immigration & Anor [2018] FCCA 3180, the Court considered an application for a partner visa made out of time and whether there were compelling reasons for not applying the criteria in Schedule 3 of the Migration Regulations 1994. At the time of the application, there was a child born of the relationship between the applicant and his spouse. The question was whether the Tribunal fell into jurisdictional error by failing to consider the best interests of the child following Article 3(1) of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Convention) (which had not been incorporated by Parliament into Australian law) when refusing the application for waiver of the relevant Schedule 3 criteria. The Court held that the Tribunal’s finding that there were no compelling reasons justifying waiver of the Schedule 3 criteria was a finding of fact and that the Tribunal did not err in failing to specifically refer to the convention in its reasons. It was not obliged to do so.

During the year, the following High Court decisions of relevance to the migration jurisdiction were delivered:

- Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZMTA; CQZ15 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; BEG15 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2019] HCA 3. The High Court of Australia (High Court), hearing three appeals together, unanimously held that ‘the fact of (CTH) Migration Act 1958 s 438 notification from the Secretary of Department of Immigration and Border Protection triggered an obligation of procedural fairness on the part of the AAT to disclose the fact of notification to the applicant for review. However, the High Court held that breach of such obligation of procedural fairness would only constitute jurisdictional error on the part of the AAT if the breach was material.

- Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30. The High Court allowed an appeal by the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection against decision of the Federal Court Full Court concerning a decision of the AAT to proceed to make decision on review without taking further action to allow or enable respondents to appear. The High Court further found that the Full Court of the Federal Court should not have exercised judicial restraint on the appeal from the Federal Circuit Court.

- Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 34. The High Court dismissed the appeal by a visa applicant, against the decision of the Full Court of the Federal Court. The High Court found that ‘although ultimately correct in the result, the majority in the Full Court of the Federal Court was wrong to distinguish between a decision involving a jurisdictional error and a decision wanting in authority’. The High Court found while there was an error of law on the part of the AAT, such did not amount into a jurisdictional error.

- Shrestha v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; Ghimire v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; Acharya v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 35. The High Court unanimously dismissed three appeals from the decision of the Full Court of the Federal Court, affirming the decision to cancel the student visas. The High Court found the Migration Review Tribunal’s reasons for decision in each case made perfectly clear that its treatment of the relevant circumstance did not impact on anything which the Migration Review Tribunal otherwise did in finding facts and in reasoning to a conclusion as to the preferable exercise of discretion.

Appeals

Family law appeals

An appeal lies to the Family Court from the Federal Circuit Court exercising jurisdiction under the Family Law Act and, with leave, the Child Support Acts. An appeal in relation to such matters is exercised by a Full Court unless the Chief Justice considers it appropriate for a single judge to exercise the jurisdiction.

There was a 33 per cent increase in the number of appeals going to the Family Court from the Federal Circuit Court during the year (see Table 3.4).

|

Notice of appeals |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

% change from

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Filed |

||||||

|

Family Court of Australia |

153 |

161 |

145 |

189 |

133 |

–30% |

|

Federal Circuit Court of Australia |

236 |

210 |

199 |

201 |

267 |

33% |

|

Appeals filed |

389 |

371 |

344 |

390 |

400 |

3% |

|

Per cent from the Family Court of Australia |

39% |

43% |

42% |

48% |

33% |

–31% |

|

Per cent from the Federal Circuit Court of Australia |

61% |

57% |

58% |

52% |

67% |

30% |

|

Finalised |

||||||

|

Family Court of Australia |

124 |

157 |

161 |

184 |

135 |

–27% |

|

Federal Circuit Court of Australia |

232 |

197 |

216 |

186 |

244 |

31% |

|

Appeals finalised |

356 |

354 |

377 |

370 |

379 |

2% |

|

Per cent from the Family Court of Australia |

35% |

44% |

43% |

50% |

36% |

–28% |

|

Per cent from the Federal Circuit Court of Australia |

65% |

56% |

57% |

50% |

64% |

28% |

|

Pending |

||||||

|

Family Court of Australia |

166 |

139 |

107 |

110 |

80 |

-27% |

|

Federal Circuit Court of Australia |

123 |

131 |

101 |

110 |

144 |

31% |

|

Appeals pending |

289 |

270 |

208 |

220 |

224 |

2% |

|

Per cent from the Family Court of Australia |

57% |

51% |

51% |

50% |

36% |

–14% |

|

Per cent from the Federal Circuit Court of Australia |

43% |

49% |

49% |

50% |

64% |

14% |

General federal law appeals

The majority of appeals and appellate-related applications in respect of general federal law proceedings are heard and determined by single judges of the Federal Court exercising the Court’s appellate jurisdiction.

Of the 1412 appeals and related actions filed in the Federal Court in 2018–19, 1081 were from decisions of the Federal Circuit Court, accounting for approximately 74 per cent of the overall appeals and related actions filed.

This compares with a total of 1025 appeals and appellate-related applications from the Court as reported in the 2017–18 annual report, an increase of over 23 per cent.

The vast majority of these appeals concern decisions made under the Migration Act 1958, with 1017 of the 1081 appeals filed arising from migration judgments of the Court in 2018–19 compared with 976 in 2017–18.

The increasing proportion of migration-related appellate proceedings is reflective of the general upward trend of the migration workload, with a large proportion of these matters proceeding to a defended hearing.

Dispute resolution

The Federal Circuit Court has grown to become Australia’s principal federal trial court. The Court’s jurisdiction and less formal legislative mandate is such that a significant number of parties present as self-represented litigants (SRLs). In family law, the Court is assisted by legal aid duty lawyer schemes. To address the needs of such litigants in the general federal law jurisdiction a number of initiatives have been established.

The general federal law, dispute resolution provisions are contained in Part 4 of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia Act 1999. The Court operates a docket management system, and referrals by judges are the most frequently used procedure in general federal law proceedings. Most mediation is undertaken by registrars of the Court, however some matters are referred to external providers.

Not all matters are equally likely to be referred to mediation. In practice, particular characteristics of some matters mean that referrals to mediation may occur infrequently if at all. Such matters include migration applications. The number of matters referred to mediation decreased from 719 in 2017–18 to 600 in 2018–19. (Table 3:5)

|

MEDIATION |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Referrals |

665 |

583 |

620 |

719 |

600 |

Table 3.6 shows the number of referrals to mediation by cause of action both as a number and as a percentage of filings. Overall, 6 per cent of filings were referred to mediation. As a percentage of matters, the cause of action most referred to mediation was human rights at 49 per cent of matters referred, followed by intellectual property and industrial matters.

|

CAUSE OF ACTION |

Filings |

Referrals |

Referrals as |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Administrative |

53 |

3 |

5.66% |

|

Admiralty |

6 |

1 |

16.67% |

|

Bankruptcy |

2885 |

15 |

0.52% |

|

Consumer |

141 |

17 |

12.06% |

|

Human rights |

86 |

42 |

48.84% |

|

Industrial |

1291 |

504 |

39.04% |

|

Intellectual property |

43 |

18 |

41.86% |

|

Migration |

5591 |

0 |

0% |

|

All filings |

10,096 |

600 |

5.94% |

Due to rounding, percentages may not always appear to add up to 100%.

Table 3.7 shows the outcome of mediations conducted in the reporting period. Not all matters mediated in the reporting period will have been filed or even referred to mediation in the reporting period. Matters that are referred to mediation at the end of the reporting period may be mediated in the following reporting period.

In the reporting period, registrars conducted 581 mediations and partially or fully resolved 362 matters or 62 per cent of matters.

Family law financial

In financial matters the Court:

- offers privileged conciliation conferences conducted by registrars of the Court

- offers privileged mediation in appropriate matters via the administered appropriation, and

- refers appropriate matters to privately funded mediation.

In 2018–19, registrars held 3080 privileged conciliation conferences and settled approximately 39 per cent of these matters.

Administered fund

The Federal Circuit Court receives an administered appropriation to source dispute resolution services such as counselling, mediation and conciliation from community-based organisations.

The Court is seeking to enhance the services provided to litigants and allow for greater flexibility in the provision of those services by utilising the fund to allow providers to provide counselling and mediation services to litigants locally in appropriate circumstances.

The major focus of the administered fund is to provide mediation services to litigants in property matters, particularly in rural and regional areas, in support of its circuit work. These services are currently provided by Relationships Australia (Victoria) who undertake property mediation where the provider is located within the same location as the litigants and in a position to offer more timely interventions.

|

CAUSE OF ACTION |

Finalised – |

Finalised – |

Finalised – |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Administrative law |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Admiralty and maritime |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Bankruptcy |

7 |

10 |

0 |

17 |

|

Consumer protection |

8 |

10 |

0 |

18 |

|

Fair work |

164 |

304 |

4 |

472 |

|

Human rights |

10 |

26 |

0 |

36 |

|

Industrial |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Intellectual property |

5 |

10 |

0 |

15 |

|

Migration |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

195 |

363 |

4 |

561 |

The use of the administered fund continues to expand as services are extended to more regional locations. This reduces the need for registrars to travel from registry locations, which impacts on the delays and services in the principal registries. It allows regional litigants to access mediation services in a timely fashion rather than waiting for registrar circuits.

In 2018–19, over 400 matters were referred for property mediation through Relationships Australia (Victoria). Of the 380 mediations that occurred in this financial year, 71.8 per cent were reported as having settled.

Initiatives in general federal law

Pro bono scheme – Federal Circuit Court Rules 2001 – Part 12

A court-based pro bono scheme is in operation similar to that which operates in the Federal Court. Part 12 of the rules sets out rules in relation to the court-administered scheme. Referrals for pro bono have generally been confined to general federal law matters. With a significant proportion of migration-related matters involving SRLs, the Court has been able to facilitate assistance to litigants. Assistance is also provided in various states by organisations such as JusticeNet and Justice Connect. The Court appreciates the generosity of those members of the profession who agree to give their valuable time voluntarily to assist in such referrals.

Small claims lists – Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney

The Fair Work Act 2009 makes provision for certain proceedings to be dealt with as small claims proceedings. An applicant may request that an application for compensation be dealt with under this division if the compensation is not more than $20,000 and the compensation is for an entitlement mentioned in the Fair Work Act 2009. When dealing with a small claim application, the Court is not bound by the rules of evidence but may inform itself of any matter in any manner as it thinks fit. A party to a small claims application may not be represented by a lawyer without the leave of the Court. Rules in relation to the conduct of proceedings in the Fair Work Division are found in Chapter 7 of the Federal Circuit Court Rules 2001.

The Court aims to minimise the number of events needed to dispose of such applications. Ideally, the Court aims to finalise these matters on the first hearing date. In Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney, the Court has dedicated lists with panel judges assigned, with the aim of disposing of such matters on the first date. Staff from the Fair Work Ombudsman are available to provide assistance on an amicus basis.

The main aims are:

- ensuring that both parties attend court at the first hearing with all relevant material. This is facilitated by having a notice with the listing that indicates the matter may be dealt with and determined on the first return date

- providing information to applicants that advises them of the type of material they may need to provide in support of their claim

- accepting documents such as Fair Work Ombudsman Inspector’s Report as evidence of the applicant

- having a registrar with some knowledge of the area available for mediation where the judges consider this to be helpful, and

- keeping it simple – an application form with instructions which guides the applicant on a step-by-step basis, and a pro forma affidavit of service.

Litigants are provided with a fact sheet, along with other resources to assist them in the process. The Fair Work Ombudsman provides staff to assist at the lists on an amicus basis and various other material is available if additional claims are raised.

Migrant Workers’ Taskforce Report

The Migrant Workers’ Taskforce Final Report was released on 7 March 2019. The taskforce was established on 4 October 2016 and was preceded by a significant number of high profile cases revealing exploitation of migrant workers. Among other things, the report stated that these cases exposed unacceptable gaps in Australia’s legal system designed to treat all workers equally, regardless of their visa status. Accordingly, the taskforce was set the specific task to identify proposals for improvements in law, law enforcement and investigation, and other practical measures to more quickly identify and rectify cases of migrant worker exploitation. The Government has subsequently agreed ‘in principle’ to all recommendations of the report.

The report makes 22 recommendations. Recommendation 12 of the Report provides ‘that the Government commission a review of the Fair Work Act 2009 small claims process to examine how it can become a more effective avenue for wage redress for migrant workers’. The report can be found at: https://docs.employment.gov.au/documents/report-migrant-workers-taskforce

Migration duty lawyer scheme – Melbourne

The Federal Circuit Court’s migration workload, particularly its hearing workload, has steadily increased since October 2001 when migration jurisdiction was conferred on the Court. Migration now represents the largest jurisdiction in the Court’s general federal law defended hearing list, with most first instance judicial review applications being filed in the Federal Circuit Court.

Migration work presents additional demands on the Court and its administration that do not arise in other areas of the Court’s jurisdiction. As many litigants in migration matters are self-represented, particularly those seeking review of protection visa decisions, there is a greater need for pro bono representation or other legal representation, particularly as legal aid is not available to protection visa applicants who are in migration detention. The Court has found it essential to set up a pro bono scheme (similar to that which operates in the Federal Court).

There is a legal aid duty lawyer scheme in respect of the Federal Circuit Court directions lists in Melbourne.

Skilled Victoria Legal Aid migration duty lawyers are present at the directions hearings and give legal advice, refer eligible clients for legal aid, and may earmark some matters for pro bono referral. The Court is grateful for this service as it facilitates the conduct of the migration matters.

Pro bono migration scheme – Brisbane

Pro bono matters are now processed through LawRight’s self-representation service as it also administers Pro Bono Connect, which is now used by the both the Bar Association and the Law Society for matching barristers and/or solicitors to particular cases as pro bono lawyers.

Pilot to assist SRLs – bankruptcy lists – Melbourne and Adelaide

With the assistance of Consumer Action in Melbourne and Uniting Communities in Adelaide, the Court has, in conjunction with the Federal Court, been able to facilitate a program of targeted financial counselling assistance to SRLs in bankruptcy proceedings. Since the latter part of 2014 in Melbourne and 2018 in Adelaide, a financial counsellor sits in the courtroom in every bankruptcy list. The registrar presiding is able to refer a SRL to the financial counsellor for an immediate confidential discussion so that the SRL better understands his or her options when faced with the prospect and consequences of bankruptcy.

In Melbourne, during the reporting year, there were 67 referrals of debtors in proceedings to financial counsellors, 58 of which have been determined. In 43 of those proceedings (74 per cent), they were resolved by consent. While statistics are not yet available from Adelaide, registrars have reported favourably about the program.

In addition, compared to the preceding five year period, the number of reviews of registrars’ decisions in bankruptcy in Melbourne fell by 69 per cent on average from the inception of the project to the end of 2017.

Child Dispute Services

Child Dispute Services (CDS) provides expert independent, social science advice and assistance in relation to disputes about children in matters before the Family Court or the Federal Circuit Court. To achieve this, Family Consultants conduct preliminary family assessments at the interim stage of a matter, provided to the Court in the form of a memorandum, or comprehensive family assessments for a final hearing, provided to the Court in the form of a family report. CDS makes information available about the different types of assessments it undertakes through fact sheets on the courts’ websites.

After its expansion in 2017–18, brought about by the Federal Government providing additional funding for new Family Consultant positions, the 2018–19 year was primarily one of consolidation for CDS. The focus has been on clinical governance, quality assurance and the professional development of staff.

Continuous professional development is critical for Family Consultants to be able to maintain and build their knowledge, expertise and competence in a field where the empirical evidence base is constantly developing. In addition to individual Family Consultants attending a raft of external training programs, the ongoing CDS professional seminar series saw a range of eminent experts deliver training on the following topics across the year:

- trauma informed jurisprudence

- orders for supervised time

- fathering and attachment

- technology facilitated abuse

- working in the specialist Indigenous court list

- intimate partner violence – an overview of the research

- parenting in the context of family violence and inter-parental conflict, and

- the impact of trauma on the developing brain.

In addition to the work undertaken by way of family assessments, CDS continues to participate in sharing its knowledge and collaborating with other service providers within the family law and broader service sectors.

Examples of this include presentations given by CDS staff in forums such as:

- Family Law Pathways network events

- the National Children’s Representatives Conference and

- court visits by international delegations.

Circuit program

The Federal Circuit Court is committed to providing services to rural and regional areas of Australia. Judges of the Court currently sit in rural and regional locations to assist in meeting this commitment. These sittings are known as circuits.

In 2018–19 the Court sat in 30 rural and regional locations as part of its extensive circuit program. Details of the circuit locations are included at page 23.

When on circuit, the Court sits in leased premises and state and territory court facilities. While the Court appreciates the hospitality of state and territory courts in enabling the Court to service regional and rural litigants, reliance on state facilities poses a number of challenges for the Court, including availability of courtrooms, hours of access, access to technology, court recording and resources such as telephone and video link facilities, and security arrangements.

The Court is aware of these challenges, not only for litigants and legal practitioners, but also staff, and continues to look for opportunities to improve facilities and resources, and thereby, the efficiency and value of circuits.

Judges of the Court travelled to circuit locations on 150 occasions (excluding Dandenong and Wollongong) throughout 2018–19. The length of these circuits varied from single days to whole weeks depending on the demands of the circuit and the distance to parent registries. In addition to those 150 weeks, there was a significant judicial presence in the Dandenong and Wollongong registries where there is a near full-time judicial presence. It is estimated that the work undertaken in the rural and regional locations equates to approximately 20 per cent of the Court’s family law workload.

In addition to attending circuit locations, judges conduct some procedural and urgent hearings by video link and telephone in between circuits. The technology provides litigants with greater access to the Court and assists in maximising the value of time spent at the circuit locations. eFiling provides litigants and legal practitioners with greater access to the Court by enabling them to file documents from rural and regional locations as opposed to attending registry locations or using standard post.

The Court has experienced an increase in the workload pressure on numerous circuits with increasing volumes of matters as well as increasing complexity of matters. The Court has a policy of not increasing circuit frequency or durations without proper consultation including having regard to competing workload demands across the country, in both registry and circuit locations, as well the budgetary pressures faced by the Court.

The Court continues to look at ways to improve the efficiency of circuits and access to justice for litigants and legal practitioners.

Complaints

The Court is committed to acknowledging complaints as soon as practicable and managing responses in an effective and timely manner. The Court’s complaint policy and judicial complaints procedure is available at www.federalcircuitcourt.gov.au.

During 2018–19, 252 complaints were received, which is on par with 2017–18 (253).

Table 3.8 provides a breakdown of these complaints by category.

|

Complaint about |

Number received |

|---|---|

|

Child dispute services |

63 |

|

Overdue judgment |

60 |

|

Legal process |

43 |

|

Conduct – judge |

40 |

|

Judicial decision |

19 |

|

Family registry |

7 |

|

Conduct – registrar |

6 |

|

Divorce |

4 |

|

Expert witness |

3 |

|

National Enquiry Centre |

2 |

|

Conduct of proceedings |

1 |

|

Electronic filing |

1 |

|

General federal law registry |

1 |

|

Mediation |

1 |

|

Privacy |

1 |

The number of complaints is relatively small and it is of concern that the largest number of complaints are in relation to outstanding decisions.

The Court has a protocol that sets a benchmark of three months, and matters that are outside this benchmark are actively monitored by the Chief Judge’s chambers.

Judicial complaints policy

The Judicial Misbehaviour and Incapacity (Parliamentary Commissions) Act 2012 and the Courts Legislation Amendment (Judicial Complaints) Act 2012 commenced on 12 April 2013.

The Judicial Complaints Act amended the Federal Circuit Court of Australia Act 1999, the Family Law Act 1975, the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976, and the Freedom of Information Act 1982 to:

- provide a statutory basis for the Chief Justice of the Federal Court, the Chief Justice of the Family Court and the Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit Court to deal with complaints about judicial officers

- provide protection from civil proceedings that could arise from a complaints handling process for a Chief Justice or the Chief Judge as well as participants assisting them in the complaints handling process, and

- exclude from the operation of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 documents arising in the context of consideration and handling of a complaint about a judicial officer.

The Parliamentary Commissions Act provides a standard mechanism for parliamentary consideration of removal of a judge from office under of the Australian Constitution paragraph 72(ii). Details of the Judicial Complaint Procedure of the Court are found at www.federalcircuitcourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fccweb/contact-us/feedback-complaints/judicial-complaints.

Judgments

In 2018–2019, 3850 judgments were settled into written format, which is a large increase from the 3466 that were published in 2017–18.

Table 3.9 provides a breakdown of judgments finalised by jurisdictional category.

|

Jurisdictional category |

Number finalised |

|---|---|

|

Administrative law |

8 |

|

Admiralty law |

1 |

|

Bankruptcy |

90 |

|

Child support (includes AAT) |

27 |

|

Consumer law |

8 |

|

Family law |

1687 |

|

Human rights |

18 |

|

Industrial law |

195 |

|

Intellectual property (includes Copyright and Trade marks) |

7 |

|

Migration |

1787 |

|

Practice and procedure |

22 |

Publication of judgments is seen as an important way to serve the public interest and reflect the Court’s commitment to open access to justice. Efforts are made to publish as many judgments as practical while also applying legal publishing standards and complying with legislative requirements restricting the publication of private information related to certain proceedings. The publication of these judgments is also seen as a way to adequately reflect the work of the Court.

To maintain and improve this administrative function, the judgments team disseminates the Court’s decisions as widely as possible and in a timely manner. All judgments that are suitable for external distribution are published to AustLII (the primary free-access resource for Australian legal information). Members of the public can also monitor and link to the latest published judgments via the Court’s website.

Copies of unreported judgments are also distributed to commercial legal publishers for inclusion in case citation databases (including LexisNexis, Westlaw AU, CCH and Jade BarNet).

In 2018–19, 105 decisions of the Court were published in commercial law report series, including the Federal Law Reports, Family Law Reports, Australian Industrial Law Reports and Australian Bankruptcy Cases.

The Court also publishes a link to the AustLII version of the judgment on its own website (the latest judgments are at www.federalcircuitcourt.gov.au).

A significant number of the Court’s decisions are delivered ex tempore at the conclusion of the hearing or soon after. Not all of these judgments are settled into a written form due to the additional time required for this task. Those that are settled are done so in response to a request from the parties or a notice of appeal, or if the judicial officer considers it appropriate to do so.

Efforts are made to increase the number of family law decisions externally published onto AustLII and commercial databases, however s 121 of the Family Law Act 1975 imposes an additional requirement on the Court in regard to these judgments. This section stipulates that published decisions of family law matters must not reveal, among other details, the identity of parties, children or associated persons to the proceedings. The judgments office devotes a significant amount of time sanitising family law and child support decisions so that they are suitable to be published.

In 2018–2019, approximately 787 family law decisions were published externally.

Analysis of performance – registry services

Family law registries

There are 18 family law registries in every state and territory (except Western Australia).

Family law registries are managed by the Federal Circuit Court but provide services to the Family Court and the Federal Circuit Court. The Federal Circuit Court has run and managed the family law registries since 1 July 2016.

This will change from 1 July 2019 when the registry services functions for the Federal Court, Family Court and Federal Circuit Court will be amalgamated into a new program under Outcome 4 – the Commonwealth Courts Registry Services.

For the 2018–19 reporting year, the key functions of the registries, as managed by the Federal Circuit Court, are to:

- provide information and advice about court procedures, services and forms, as well as referral options to community organisations that enable clients to take informed and appropriate action

- ensure that available information is accurate and provided in a timely fashion to support the best outcome for clients

- encourage and promote the filing of documents and management of cases online through the Portal

- enhance community confidence and respect by responding to clients’ needs and assisting with making the court experience a more positive one

- monitor and control the flow of cases through file management and quality assurance

- schedule and prioritise matters for court events to achieve the earliest resolution or determination

- manage external relationships to assist with the resolution of cases, and

- assist in the evaluation of caseloads by reporting on trends and exceptions to facilitate improvements in processes and allocation of resources.

Counter enquiries

Staff working on the counters in family law registries handle general enquiries, lodge documents relating to proceedings, provide copies of documents and/or orders and facilitate the viewing of court files and subpoenas. Registry service staff provide an efficient and effective service when dealing with litigants in person and the legal profession face-to-face at registry counters across Australia.

In 2018–19, 167,274 clients attended family law counters and 90 per cent were served within 20 minutes. The decrease in counter enquiries compared to 2017–18 was expected given the enhancements to the portal and the support provided to clients by court services staff in order to file electronically.

Document processing

Family law registries receive and process applications lodged at registry counters and in the mail. In 2018-19, the service target of 75 per cent being processed within two working days of receipt was significantly exceeded (98 per cent of documents lodged by mail and at counters were processed within that timeframe). This is consistent with the result from 2017–18.

National Enquiry Centre

The NEC continued to provide family law telephone, email and live chat support services to the Family Court and Federal Circuit Court in 2018–19.

The NEC’s responsibilities include:

- first telephone contact to the courts via the 1300 number

- first email contact to the courts via enquiries@familylawcourts.gov.au and support@comcourts.gov.au

- first contact to the courts via live chat

- a large proportion of telephone and email contacts from existing parties, lawyers and other court stakeholders

- support for users of the Portal including the Family Court of Western Australia and the Federal Court

- after hours service

- printing of divorce orders

- printing of event-based fee statements

- processing of proof of divorce requests, and

- Twitter notifications of procedural and registry information.

Enquiries are received via three public channels: telephone via the 1300 number; emails; and live chat. The NEC’s focus is to provide parties and stakeholders with appropriate information as efficiently and simply as possible through these channels.

Callers to the 1300 number are provided with general background and support information in a welcome message before being placed in a queue for the next available operator. Emails and live chats are monitored by staff trained in responding to written requests. With the growth of Portal registrations, Portal support was a major factor contributing to the work of the NEC in 2018–19.

The NEC regularly refers parties to various stakeholders including 1800 Respect, Family Relationships Advice Line (FRAL), legal aid, government agencies and community legal centres. The NEC maintains a close relationship with FRAL and legal aid centres and regularly consults with them.

The NEC continued its commitment to support staff in their work and encourages a collaborative workplace by:

- providing ongoing coaching and training

- enhancing wellbeing by providing ergonomic training assessment to all staff

- providing peer support and mentoring